Fertility and subsistence - a cross-cultural analysis

Status: Ongoing

Co-PI: Rebecca Sear (LSHTM).

Collaborators: Colette Berbesque, Jeremy Koster, Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, Heidi Colleran, Karen Kramer, Siohban Mattison, Brooke Scelza, Mary Shenk, Jonathan Stieglitz, John Ziker, Cody Ross, Katie Starkweather, Luis Pacheco-Cobos, Ryan Schacht, Sheina Lew-Levy, Adam Boyette, Shane Macfarlan, Christina Moya, Jennifer French

BACKGROUND

There has long been academic interest in the relationship between fertility and mode of subsistence, spanning anthropology, demography and archaeology. From a prehistoric perspective, archaeologists have pointed to significant population expansions, often referred to as the Neolithic Demographic Transition, due to significant increases in fertility associated, and arguably caused by, the onset of agriculture 12,000-6,000 BP (Diamond, 2002; Diamond and Bellwood, 2003; Bocquet-Appel, 2008; Guerrero, Naji and Bocquet‐Appel, 2008). Demographers have sought to better understand ‘natural’ human fertility prior to the secular decline in fertility in ‘controlled’ population (Campbell and Wood, 1988), while anthropologists, and in particular, human behavioural ecologists, have long explored the relationship between the environment and reproductive strategies, such optimal fertility in mobile foraging communities (Blurton Jones and Sibly, 1978).

Across these different disciplines, fertility has been hypothesised to increase with the domestication of plants and livestock, and thus, hunter-gatherers are expected to have lower fertility compared to horticulturalists, pastoralists and agriculturalists (Roth, 1981; Hitchcock, 1982; Roth and Ray, 1985; Hewlett, 1991; Bentley, Goldberg and Jasieńska, 1993; Sellen and Mace, 1997; Kelly, 2013). From the archaeological record, average population growth rates are documented to have risen from <0.001% per year to 0.04% during the early Neolithic (Bandy, 2005; Bellwood and Oxenham, 2008; Cohen and Crane-Kramer, 2007; Downey et al., 2014; Hershkovitz and Gopher, 2008; Wells and Stock, 2007; Willis and Oxenham, 2013; Zahid et al., 2015). There are several possible mechanisms for such population increases associated with changes in diet and activity patterns that accompany agriculture. First, more sedentary and food producing women are argued to experience increased energy availability allowing them to re-invest this into fertility (Ellison, 2003; Starling and Stock, 2007; Bocquet-Appel, 2008). Second, domesticated grains represent a concentrated source of carbohydrates, which increases the available calories and reproductive value (Hausman and Wilmsen, 1985; Herrera, 2000; Hardy et al., 2015). Third, agricultural produce is often used as supplementary foods to speed up weaning and shorten interbirth intervals (Sellen, 2006). While current evidence suggests that the first farmers were no more productive than foragers (Bowles, 2011), and that in contemporary foragers increased agricultural dependence is not necessarily associated with productivity (Dyble et al., 2019), changes in female work patterns between modes of subsistence might have energetic consequences which impact their fecundability (the likelihood of conception in an given month of exposure (Campbell and Wood, 1988)). For instance, increased time in food processing and a reduction of foraging activities, reduces aerobic exercise (rather than productivity) (Kelly, 2013), suggesting that women’s energetics may play an important role in the demographic correlates of subsistence systems.

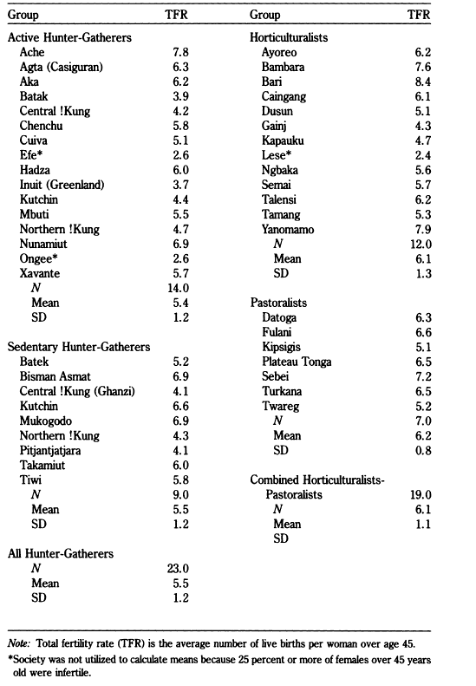

However, there are a number of studies from current populations which do not support the hypothesis that populations with higher involvement in food production have higher fertility. Campbell and Wood (1988), Hewlett (1991) and Bentley and colleagues (1993) all compared the average TFR of different subsistence types (hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists and agriculturalists), finding little difference between the groups. Focusing on (Hewlett, 1991) results, which are presented in Figure 1, it is apparent that there is wide variability in TFR in the entire sample, ranging from 2.4 – 8.4, mean 5.6 (SD = 1.4) which does not vary significantly between population types: the hunter-gatherer mean TFR was 5.5 (SD = 1.2), pastoralist TFR= 6.1 (SD = 0.8) and the horticultural mean TFR was 6.1 (SD = 1.3). As a consequence, it is not possible to argue that farmers or pastoralists have higher fertility than foragers, in keeping with Campbell and Wood’s (1988) results, which indicated that “hunter-gatherer populations [TFR] appear to be just as variable as tribal populations, which appear to be just as variable as peasant populations” (P. 56).

Figure 1: Table of TFR reported in Hewlett 1991

Later studies conducted by Bentley, Jasienska and Goldberg (1993) and Sellen and Mace (1997) ran similar analyses removing transitioning populations from the analysis, reducing the sample size. While Bentley, Jasienska and Goldberg (1993) found that the TFR of agriculturalists was significantly higher than non-agriculturalists, they did not find a significant difference between hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists. Bentley and colleagues conclude they cannot use this data to make predictions about fertility levels based on subsistence alone. Finally, Sellen and Mace (1997) used continuous estimates of dependence on difference forms of subsistence, finding that a 10% increase in agriculture was associated with a 0.2 increase in live births. However, this relationship was only apparent in mobile populations, not permanently settled groups. Overall, while the results indicate that foragers mean TFR tends to be lower than other subsistence types, results are mixed, contentious and rarely reach statistical significance given issues of sample variability and statistical power.

Problematically, such mixed results leave no clear conclusions about the relationship between subsistence type and fertility, and as a review of the literature indicates, this topic is no longer actively explored despite various sources reporting that hunter-gatherers have lower fertility that other populations (Kelly, 2013). Furthermore, there are a number of issues with the previous studies which may produce these mixed results, which can be developed and improved upon in future analyses. These issues can be reduced down to i) a lack of statistical power when comparing means; ii) variability within subsistence types; iii) a lack of boundaries between subsistence types; and iv) data quality issues; These will now be briefly discussed in turn.

Issue i: Variability and lack of statistical power

In Bentley and colleagues’ sample, while the mean TFR is 5.6 for hunter-gatherers and 6.6 for agriculturalists, the standard deviation (SD, σ) of TFR was 1.39. A high SD indicates the mean (or median) does not accurately represent the wider range of values. Given this SD and a sample size of 5-11 hunter-gatherers, this analysis does not have the power to detect a 1.1 change in TFR the majority of the time, even if it was there. Therefore, previous analysis based on categorical subsistence divisions null results may be due to a Type II error given the high variability in TFR between populations within the subsistence category, as highlighted in Table 1.

Issue ii: Variability within subsistence types

Issue 1 highlights variability in TFR within the subsistence types, however the categories themselves include variability on more measures than just ‘mode of subsistence’. Modes of subsistence are associated with changes in social and political organisation, degrees of sedentarisation, food storage, wealth accumulation, inequality and varying levels of contact with other populations (Hayden, 1995; Price and Gebauer, 1995; Piperno and Pearsall, 1998; Cohen and Crane-Kramer, 2007; Kelly, 2013). However, these are not uniformly expressed in all populations within a subsistence category. For instance, some hunter-gatherers have hierarchical social and political systems, are largely immobile and as a result have significant wealth and food storage (Woodburn, 1982). Each of these traits may be independently associated with fertility, and the ‘lumping’ of them into one category hides these relationships. How contact with other populations may impact fertility rates is apparent in the some of the lowest and highest TFRs reported in hunter-gatherers: The Efe (Democratic Republic of the Congo) had a reported TFR in 1987 of only 2.6 (Bailey and Aunger, 1995). Researchers have highlighted the high rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) across Africa, resulting in pathologically low levels of fertility (Pennington and Harpending, 1991; Pennington, 2001). The Efe have a primary sterility rate of 28% (Bailey and Aunger, 1995), producing a significantly lower TFR compared to neighbouring Pygmy populations (Aka = 5.5, Mbuti = 5). At the other end of the scale, the Agta have documented TFRs between 6.3 to 7.7 (mean= 6.93) over the last 60 years. While engaging in foraging, the Agta have also historically traded foraged resources for tubers and rice with nearby farmers (Peterson, 1978). Domesticated grains represent a concentrated source of carbohydrates, which improves nutritional condition and thus reproductive potential (Herrera, 2000). These causal relationships have yet to be tested, however, it makes the point that population variability matters.

Issue iii: A lack of clear boundaries between subsistence types

Subsistence types are not bounded, innate entities that can be used as an explanatory variable (Kelly, 2013). They are open to interpretation and often influenced by individuals’ ideological stand points (Panter-Brick, Layton and Rowley-Conwy, 2001). Taking the example of hunter-gatherers, it seems at first this is a simple economic category describing groups who lack the domestication of plants or animals. However, there is extreme variability in these subsistence activities; from Cheyenne Native Americans who hunted 80% of their food, to the Inuit who fished (primarily seals) all but 5% of their diet, or the Hadza or Ju/’hoansi who gathered 65-85% of their food (Kelly, 2013). Furthermore, since the earliest ethnographies most hunter-gatherers have derived some of their diet from non-foraged sources. Thus, strict adherence to the ‘absence of domestication’ definition of hunter-gatherers would eliminate most known populations (Washburn and Lancaster, 1968). Rather, how hunter-gatherers have been defined throughout the 19th and 20th centuries is often based on ideology or modelled on a few of the best studied groups (Panter-Brick, Layton and Rowley-Conwy, 2001). Hunter-gatherers were originally defined as male-dominated patrilocal bands (Service, 1962), later an emphasis was placed on mobility and egalitarianism as hunter-gatherers became the ‘original affluent societies’ (Sahlins, 1968). More recently, they were defined by their marginalised role within globalised world-systems (Headland and Reid, 1989). This is important because it highlights the flexibility in definitions, and that hunter-gatherers, like other foraging populations are not discrete entities, suggesting why there is so much overlap in TFR between subsistence groups.

Issue iv: data quality issues

While the first issues dealt with variability within and between modes of subsistence, this last one considers the methodological issues in demographic data collection. As documented by Hewlett (1991), data sources vary in terms of the reliability of demographic trends. In populations without written demographic records, fieldworkers rely on self-reported genealogies. However, self-reports do not necessarily produce a fully accurate demographic record; recall bias is common, leading to an underreporting of births, miscarriages, stillbirths and infant mortality due to either forgetfulness, a lack of cultural recognition of a ‘birth’ or simple miscommunication (Cronk, 1991; Page et al., 2019). While some researchers go to great lengths to ensure the reliability of self-reports with increase probing, cross-references and longitudinal data collection (Hill and Hurtado, 1996; Early and Headland, 1998; Howell, 2010; Marlowe, 2010; Headland, Headland and Uehara, 2011), other sources, particularly older ethnographic reports are questionable sources of demographic data (Hewlett, 1991). Additional issues include small sample sizes from non-industrial populations how are especially vulnerable to stochastic (random) demographic variation. In terms of long-term growth or decline, in a large population, individual events are ‘averaged’ out, while in smaller groups this random variation has disproportionate influence; patterns of growth and decline are far more extreme and volatile in small populations (Richter-Dyn and Goel, 1972; Mace et al., 2008). Consequently, in a small population an extremely low or high fertility rate may be the outcome of the size of the sample. Finally, cross-cultural studies use subsistence and fertility data from different time points, or average across different populations of the same ethnolinguistic group (Sellen and Mace, 1997). Given the wide variable in TFR reported in Agta populations (as well as large differences in mortality, livelihoods, behaviour and socioeconomic position, see (Page et al., 2016, 2019)) across a relatively small geographic distance, for instance, such practices may be hiding within population trends.

So, where do we take this literature from here? What can be done to improve the quality of the analysis?

Proposed methodology

This proposal attempts to overcome these previous difficulties by looking at the relationship between subsistence and fertility at the individual level in a wide range of subsistence-level populations, expanding on the methodology applied in Page et al., (2016). This method correlates individual involvement in different forms of subsistence (as a proportion of total activities, i.e. 75% hunting and gathering vs. 25% of time in cultivation) and degree of mobility (residential camp movements) with (age-controlled) fertility. As a result, there is no need to place populations into somewhat arbitrary subsistence groups for analysis, make assumptions about how ‘traditional’ or not they are or use mean values which disregard the intra-population variability. This analysis demonstrated that within this one population (the Agta), cultivation and sedentism was positively correlated with age-specific fertility ratees (Page et al., 2016). However, this is only one population of hunter-gatherers in a very specific socio-ecological context with a small sample (n = 117). To further this research question, a similar methodology should be applied in a wide range of populations. This method accounts for the following:

-

Within populations there are wide variations in fertility. Just as the mean TFR on a mode of subsistence may be unreflective of the distribution, the same is true of intra-population variation.

-

Individuals within a population demonstrate varying engagement with foraging (hunting, gathering and fishing), cultivation/horticulture and pastoralism. These differences are also likely related to differences in mobility and settlement. This method allows an exploration of the relationship between degree of engagement in different activities and fertility, as well as pulling apart the relationship of settlement from subsistence.

Project link: https://osf.io/6vbj4/